CAMBRIDGE - Carving turkey the traditional way has never been a strength for Harvey Baumann, a plastic surgeon who practices in Providence. "I get one or two good slices, and then it looks like an explosion in a meat factory," he says. "It's embarrassing. Here you are a surgeon and you can't carve a turkey."

CAMBRIDGE - Carving turkey the traditional way has never been a strength for Harvey Baumann, a plastic surgeon who practices in Providence. "I get one or two good slices, and then it looks like an explosion in a meat factory," he says. "It's embarrassing. Here you are a surgeon and you can't carve a turkey."

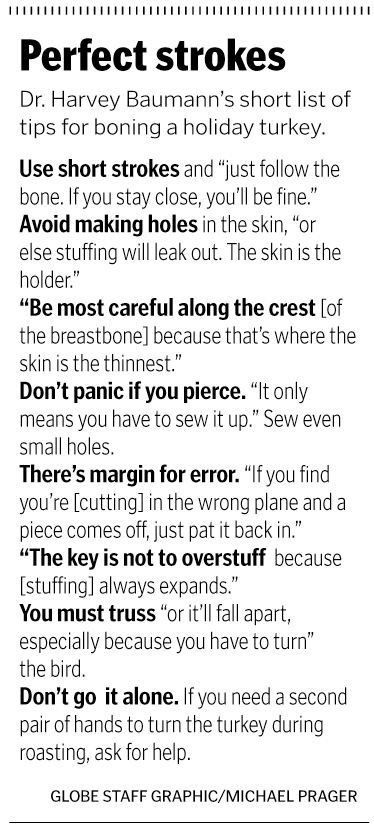

After a few such scrapes, someone else might have surrendered his sword to a brother-in-law. But Baumann's solution was different: For decades now, he has boned the bird before cooking it. Using surgical equipment, he removes the breastbone and the thigh bones, then stuffs the bird and reshapes it. Not only does it cook faster, he says, but "usually we have 20 to 22 people here for Thanksgiving dinner, and when you start slicing it like a sausage, people are always amazed. And you get the skin, some white meat, some dark meat, and some stuffing, all in one slice."

Baumann's inspiration was Julia Child, whose show was often on patients' TV screens when the doctor made surgical rounds at Beth Israel Hospital in the 1960s. "We used to watch her dissections, and she was better than many surgeons. She was a real hero to the residents. One day I saw her doing a turkey, and that's when I started doing it."

With a green-handled Bard Parker No. 10 surgeon’s scalpel and Ethicon-brand black braided silk that comes already threaded on needles in sealed packages, Baumann begins. He aims his scalpel at the back of the turkey's neck and presses and pulls down to slice through the skin. Then he returns to the top and with sure, short strokes starts separating meat from carcass along the backbone.

Next comes the rib cage, the easiest real estate: "You could almost do it with your fingers, like the surgeons do," he says. It gets tougher again at the upper thigh. His purpose is to leave legs and wings intact so that after trussing, the bird still looks like a bird. Even more importantly, he wants to preserve them for guests for whom it wouldn't be Thanksgiving dinner without a drumstick. But that still means the upper part of the thigh, down to the knee, has to be excised. It requires severing tendons at both ends and removing the meat from the bone.

Upon reaching the tailbone, Baumann returns to his starting point and begins cutting down the other side with the same short strokes. The sharp scalpel makes this go smoothly. Even so, explains Baumann, the tool doesn't make the task. "I'm just used to a scalpel, and it's sharper than the usual boning knife, but you don't need one," he said.

He leaves the breastbone until last. "You have to be most careful at the crest [of the bone], because that's where the skin is the thinnest." Even after taking time to pluck stray feathers, he's through in about 40 minutes.

Then comes part two, in which he removes extraneous fat (but not any skin) and sprinkles lemon juice, cognac or brandy, and allspice into the cavity. Then he starts to sew where the backbone used to be. He also repairs any holes that resulted from careless processing.

The thread weaves in and out of the skin. "It's black, so your guests won't eat it, and it's a natural silk. You could use cotton, too. You want to use a natural fiber that won't do anything to the flavor of the bird," he says. He's performed the procedure many times, not only for his own table but for friends and neighbors, as many as five or six times in a season.

He doesn't add the stuffing until he has partly sewed up the backbone area. When the seam has been completed, it's time to truss. In addition to tying the breast, the legs and wings must be bolstered, he says, in order to reshape the bird.

The surgical procedure has taken the doctor 80 to 90 minutes, which some might consider laborious. "You have to like doing it," Baumann concedes. "But when you put it on the table before people who've never seen it done, their first expression is just wonderful."

- Log in to post comments