Submitted on

Practically every human on the planet throws stuff away every day without giving much thought to where "away" is and how the stuff gets there. This morning in Seattle, a team of MIT researchers outlined their scheme to do just that.

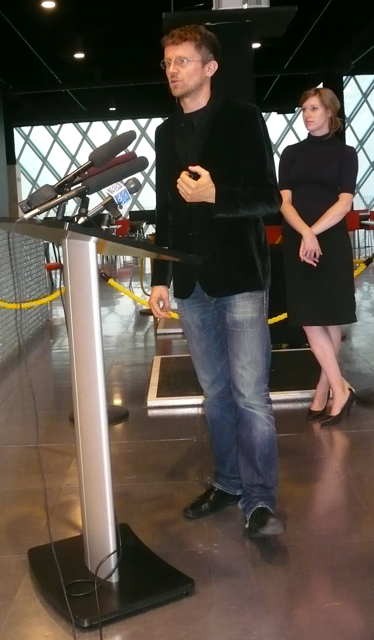

The so-called Trash Track project has electronically tagged more than 500 items of refuse, culled from several source categories, and is tracking their movements in hopes of learning more about what Professor Carlo Ratti [at microphones, in photo], team leader and director of the SENSEable Cities Lab, calls "the removal chain," which he contrasted to the much better known business supply chain.

Speaking to reporters at the Seattle Central Public Library, where a video art project about the project (link to sample image) was unveiled before a public forum got underway, Ratti expressed hope that in addition to providing information, the project may prompt people to change their behavior.

Speaking to reporters at the Seattle Central Public Library, where a video art project about the project (link to sample image) was unveiled before a public forum got underway, Ratti expressed hope that in addition to providing information, the project may prompt people to change their behavior.

Within five or 10 years, he added, the information gleaned from the use of the electronic tracers could "100 percent accurating sorting [of trash] with RFID tags."

The lab's associate director, Assaf Biderman, said the tracking idea has arisen with the advent of "ubiquitous computing," in which wireless network begin to blanket cities, allowing all sorts of data to be collected in real time. "This will allow us to inform citizens better [about] how we interact with waste," he said.

The experiment is also being conducted in New York City, but with only about 30 tagged items, said Jennifer Dunnam [behind Ratti in photo], a team member organizing volunteers. Seattle was chosen because of its status as a preeminent green city in the nation.

One segment of the sample was gathered from 15 volunteers who contributed 10 items each. Team members went to each donor's home for brief interviews about each item's origin. One was a can the donor had purchased 30 minutes prior; another was a motor the donor had had for 20 years.

Dunnam said an additional 70 items were brought to the library by people responding to an open call for trash.

"The rest, we did ourselves," she said. Dunnam conceded that the trash from volunteers was likely to have been disposed of responsibly, which might not reflect the actions of the general populace. She did say that "we found computers on the side of road and tagged them and left them there. Hopefully, they'll go where they're supposed to."

The art installation, available for viewing at the library until Oct. 11, recounts the journeys of specific items, including where the item was disposed, how many miles they traveled, over what path, and in what period of time, and what category of waste it belongs to.

Dunnam said the "End of Life" group, a team of life-cycle analysts at MIT, advised the lab how the study sample should be constituted, and electronic waste was a major component. Among 10 items that came onto the screen, which was the backdrop for the press conference, were five e-waste pieces: a computer processor, a PC tower, a VCR, a cellphone, and a TV. The others were newspaper, an inkjet cartridge, an aluminum can, yard waste, and snail poison.

Dunnam said some items were much easier to tag than others. Lightbulbs were tough, for example, but "fabrics were good," she said, because the liquid adhesive attached thoroughly.

Ratti said items are still in transit, but data gathering and analysis should be complete in about three months.

Project sponsors include Waste Management and Qualcomm.

- Michael's blog

- Log in to post comments